Lab Grown Diamonds Biggest Disruptor in the

The Durbin Amendment Explainedby Anisha on March 3, 2011

The Durbin Amendment, a last-minute addition to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, has sparked fierce debate. [Update July 6, 2011: After the Durbin Amendment barely survived a challenge from Sen. Jon Tester, the Federal Reserve ruled that debit interchange fees would be capped at 12 cents plus 0.05% of the transaction, with the possibility of an additional cent if certain criteria are met. Each debit card should be able to be processed on at least two independent networks, and the rules will begin to take effect in October. This ruling is generally seen as more favorable to the financial industry than expected. For a complete rundown, check out our analysis of the Fed’s final ruling.]

The amendment is rather complex, but the two provisions that are still being debated, pending the Federal Reserve’s July 21, 2011 decision, are:

- A cap of 7 to 12 cents on most debit card swipe fees, a decline of about 80% from present levels

- The introduction of competition, by giving merchants a choice as to which debit network they process transactions over. For example, present arrangements effectively force merchants to process many Visa transactions over the STAR network, even if competitors like PULSE and NYCE offer to conduct the same transaction at a lower processing price.

The provisions that are already in place include:

- Merchants can impose a $10 minimum on credit card transactions (this number can be adjusted by the Fed as they see fit). Previously, Visa and MasterCard banned this practice in their merchant agreements.

- Merchants are allowed to give discounts at the register to those who pay with cash or debit cards. Previously, Visa and MasterCard banned this practice in their merchant agreements.

Banks and credit unions are against the amendment, because debit card swipe fees mostly accrue to the financial institution that issued the debit card. Card issuing banks typically take in about 1.3% of every dollar you spend on your debit card, as a fee from the merchant. This amounts to nearly $3 billion a year of very high profit margin revenue for Bank of America, for example, a number which looks to decline by ~80% unless Congres, the Department of Justice, or the Federal Reserve intervenes.

This fee is supposed to cover the risk of fraud, transactional costs, and other overhead, but due to the lack of negotiating power on the merchant side, the fee is now a major source of profit margin at every bank that offers checking accounts. Subsequently, competition between banks has caused this profit center to be used in subsidizing free premium services, like free checking accounts and surcharge-free ATMs. If this fee were to drop to 7-12 cents per transaction, as proposed by the amendment, this would create a large wealth transfer from debit card issuers to merchants, and will likely end many free premium services at banks.

The amendment’s supporters in Congress theorize that the wealth transfer from the banks to the merchants will result in lower prices for all consumers, as competitive forces between merchants force them to pass on lower costs to customers, in the form of lower prices.

Protecting The Little Guy, Fail

The swipe fee cap technically exempts financial institutions with assets of $10 billion or less. In theory, this exempts all but 3 out of the 7,000+ credit unions. However, credit unions are aggressively lobbying against the amendment. They fear that the provision requiring multiple network routing options will make the small bank interchange cap exemption impossible to enforce. For example, Visa already promised to honor the two-tier pricing system, and would process a small institution’s transaction at the current price. However, the networks are not required to differentiate between large and small banks. Even if Visa’s STAR network offered to route a debit transaction at the “exempt” 1.5% debit interchange rate, the existence of a competitive option allows the merchant to route the transaction through NYCE instead for 12 cents. Therefore the credit union would receive some fraction of 12 cents for the transaction, rather than ~1.3% of the transaction.

The Visa-MasterCard Duopoly

Proponents of the amendment allege that merchant interchange fees have skyrocketed relative to the cost of processing the transactions. The interchange market is largely uncompetitive: Visa and MasterCard effectively set the interchange fees for all merchants. Merchants can choose not to accept Visa and MasterCard, but this is not practical for most. The Durbin amendment’s attempt to reduce prices is two-pronged: first, the mandatory introduction of competition, and second, a limit to fees in order to correct for the market failure resulting from what is essentially a duopoly.

U.S. swipe fees are, overall, uncompetitive when compared to European countries, where anti-trust regulation has broken the chokehold of Visa and MasterCard. U.S. debit interchange fees are higher than the European Union average but not egregiously so; the true effect of uncompetitive pricing is seen in the interchange fees charged on credit card transactions, where the U.S. is by far the highest.

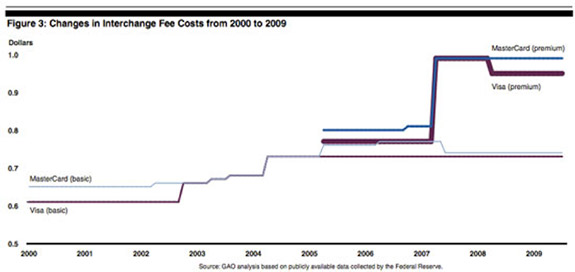

Most notably, the fees on some premium credit cards diverged greatly from the rest of the industry in conjunction with the 2007 IPO’s of both Visa and Mastercard, likely because of pressure to juice profits for public shareholders:

Onerous credit fees are ignored

Because of the difficulty of differentiating prices for goods based on the method of payment, merchants generally factor the exchange fees into the sticker price, or absorb the cost themselves. As a result, whether a consumer pays with cash, debit, credit or rewards credit, he will see the same price (one exception is in gas prices, where the limited number of products offered allows for price differentiation). However, merchant exchange fees for credit cards, and rewards credit cards in particular, are significantly steeper than debit card fees.

One feature of monopoly pricing is that the card network can, as much as they are able, set different prices to maximize how much it believes different groups will pay. So, for example, a Visa Signature Preferred rewards card nets a 2.5% interchange fee at a restaurant (which has little bargaining power), while a Visa Classic transaction may cost a large supermarket only 1.15% (because Visa wouldn’t want to risk, say, Wal-Mart walking away). By comparison, in France, a credit card with an embedded security chip costs all merchants 0.22% of the transaction plus 10 Euro cents, while the least secure (and thus most expensive to cover) method of payment costs 0.3% plus 10 Euro cents (there is virtually no difference by way of fees with Visa versus MasterCard). The intricacies of pricing, and the emphasis on the lucrative, oft-used reward credit cards, speak to market inefficiencies.

Are the fees necessary to fund fraud protection?

The major card networks allege that the interchange fees are necessary for fraud protection efforts, and to limit consumers’ losses in case fraud does occur. However, improving technology should have driven down the cost of fraud protection, not increased it. Jamie Henry, Wal-Mart’s director of payment services, argued that credit card issuers have deliberately kept chip-and-PIN technology from U.S. cards because security improvements would remove the justification for high merchant exchange fees. “Lower interchange would push the industry toward chip-and-PIN. We would see more financial institutions become interested in controlling fraud. It would be more difficult to pass [fraud] costs on to merchants.”

In response to proposed regulation, banks cry foul and threaten tightened credit, higher fees and steeper interest rates should the proposed regulations take effect. Some have also threatened per-transaction spending caps on debit cards, at $50 or $100, rendering debit effectively useless in paying for groceries, restaurants, or plane tickets, and driving customers toward more lucrative credit cards.

However, not-for-profit credit unions are also stalwartly opposed to the amendment, and for much the same reason: they fear that they will have to cut services or increase fees in response to an increased bottom line. They may have more substance to their claims than for-profit banks.

How Durbin hopes to ease the burden on consumers and merchants

The Federal Reserve believes that merchant exchange fees far exceed the cost of fraud protection. They further believe that the steep markups persist because the two major card networks, Visa and MasterCard, have such control over the credit and debit card markets that merchants, card issuers and consumers have no choice but to accept the prices that they set.

In order to correct this, the Fed proposed a cap that it believes accurately reflects the true cost of securing the debit cards used. If they have correctly judged the cap, banks will not suffer a loss to their bottom line, and will continue to provide the same services to consumers while merchants are able to offer better prices. They also introduce competition to previously monopolistic markets by requiring each debit card to be covered by at least two networks. However, the amendment fails to address credit card interchange fees, which are significantly higher than debit.

Although the regulations make an exception for small institutions, this exemption is meaningless as card issuers will have to accept the lowest exchange fee offered, whether or not it covers their security costs. This is an undue burden on credit unions, which are generally smaller and pay more to protect their customers.

This is not to say that the “swipe” fees are grossly overpriced, and that government reform of the market will not benefit consumers. However, the Federal Reserve must be careful to preserve the advantages offered by credit unions.

The following infographic, which we released last April, gives further details about how interchange fees affect merchants and banks:

Sincerely,

Jerry Whitehead

Pawnshop Consulting Group, Inc.

www.pawnshopconsultinggroup.com

CLICK HERE TO REGISTER FOR THE SYMPOSIUM

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLTETTER/BLOG

954-540-3697